What does the tail of a peacock, the antlers of a deer and pheromones in rat urine have in common? These are sexually dimorphic traits - primarily seen in males- and have evolved with the sole purpose to attract mates. Sexual selection gives rise to traits that aim to maximize reproductive success, often at the expense of survival due to the demands it places on the signaler. An individual’s fitness determines how it copes with this cost, leading to variation in strength of sexual signal which females use to choose a mate.

In rodents, such social information can be relayed by male odors, often via urinary cues. A putative candidate for a sexual signal in rats is Major Urinary Proteins (MUPs) which is a member of the lipocalin family that transports small hydrophobic molecules (steroids and lipids). It is secreted in copious amounts in the urine which is a common communication mode of rats, making it a good way to advertise sexual fitness. Work in rats has demonstrated the sufficiency and necessity of MUPs to attract females. We show that MUPs mediate sexual signaling in a dose dependant manner and we have correlated female preference for males with more MUPs. Moreover, a dynamic sexual signal will also be open to manipulation. Parasites are known to exploit such avenues to enhance transmission efficiency. We have used a relevant perturbation model in Toxoplasma gondii and have shown that it manipulates mate choice, causing females to prefer infected male rats and is sexually transmissible.

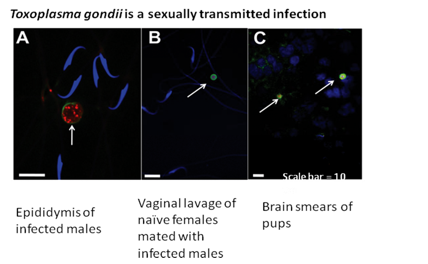

Evidence of sexual transmission of Toxoplasma. The Toxoplasma cysts are fluorescently stained (red & green) to show presence at different stages; male reproductive system, female reproductive tract after mating, and in pups (born from these matings). Picture adapted from Daas et al. 2011. (Picture adapted from Daas et al. 2011.)

Evidence of sexual transmission of Toxoplasma. The Toxoplasma cysts are fluorescently stained (red & green) to show presence at different stages; male reproductive system, female reproductive tract after mating, and in pups (born from these matings). Picture adapted from Daas et al. 2011. (Picture adapted from Daas et al. 2011.)

This is interesting as females detect and avoid parasitized males- this discrimination is often based on phenotypic traits. This discrimination benefits the hosts by reducing chances of spread of infections and choosing for heritable resistance that can be inherited by offspring. Thus, coevolving parasites will look to bypass this obstacle of sexual selection and so a parasite that can enhance sexually selected traits of a host will benefit from blunted selection pressure from the host and gain advantage of transmission. To this end, we show that T. gondii infected male rats have greater levels of MUPs in their liver (a major production site) and urine, giving credence to idea of MUPs as a sexual signal.

Contributed by Anand Vasudevan, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.